Cabinet de lecture

Musée de la Ville d’eaux, Spa

28/08 – 14/11/2021

03/04 – 13/11/2022

Part of 7 Walks (resolution), a research project by Vermeir & Heiremans

Vitrine # 02

Liberty, Equality, Justice.

And Property?

Spa has been the scene for revolutionary activities and a strong movement towards democracy and the rights of men. The right to property has been an enduring question. Jean-Guillaume Brixhe (1758 – 1807) a notary and mayor of Spa and Laurent-François Dethier, a lawyer and the mayor of Theux, were leaders of the Franchimont revolution of August 1789. Dethier was the president of the Congress of Polleur, and Brixhe was appointed secretary.

Taking the Liège Revolution of August 1789 as the motivation to change the system in place, representatives of the five districts of the marquisate of Franchimont met from 26 August 1789 to 23 January 1791, first in a meadow in the hamlet of Polleur, then in Theux and in Spa. They held twenty-five meetings which together are known as the Congress of Polleur. On 16 September 1789 the Franchimont nation proclaimed a Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. This major text was inspired by the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, but was in some respects even more revolutionary.

This progressive spirit was still alive in mid-19th century Spa. French political refugees, fleeing the coup d’état of Napoleon III in 1851 found refuge with the journalists Felix and Alexandre Delhasse, citizens of Spa. We find Emile Deschanel, Etienne Arago, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Victor Hugo, Jules Hetzel, Henri Rochefort, Edgar Quinet, Théophile Thore-Burger, Victor Considerant, Louis Blanc visiting or living in Spa. Felix Delhasse was a member of the secret society la Charbonnerie. The pseudonym he used for himself was ‘babeuf’. He was a disciple of its founder Filippo Buonarotti who was also a political refugee in Belgium. Buonarotti’s book The History of the Conspiracy of Equals (1828) related the failed coup in France of Grachus Babeuf in 1796, who wanted to restore the progressive 1793 constitution, overthrow the Directory and replace it with an egalitarian republic.

Babeuf rejected the notion that equality before the law itself was sufficient to define societal equality, and in that way placed a strong emphasis on the abolition of private property. A Manifesto of Equals was written by the conspirators proclaiming that the land belongs to no one and the fruits of the land to all. Funnily enough the manifesto also said: ”Let all the arts perish, as need be, as long as real equality remains.” But this was fiercely contested by the co-conspirators. The History of the Conspiracy of Equals had a strong influence on the progressive movements in the mid-19th century. ‘Cabinets de lecture’ had been installed in Spa and furnished by Jules Hetzel, a French publisher, with critical works by Victor Hugo and other forbidden books. Despite the hospitality to political refugees, the national security ordered the Spa police to keep a close eye on all these suspected subjects taking the Spa waters.

Hetzel also published the works of the French philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Proudhon befriended Felix Delhasse in Brussels when finding refuge under a tree during a storm. Proudhon was hosted regularly in Spa, in the Hotel Irlande. In 1840 Proudhon wrote What is Property? From this essay stems his infamous words “Property is theft!” His system, known as mutualism, however did not advocate the abolition of property. Proudhon, instead, wanted to abolish the privilege that he believed property granted to its owners. He thus advocated usufruct, which meant the right for people to use somebody else’s property, so that the proprietor—capitalist or landlord—could not live off the fruits of somebody else’s labor. To later socialists, Proudhon’s influence was marginal. Instead he remains famous today as the father of anarchism. The slogan “Property Is Theft!“ became a platitude, and circulated without the theoretical nuance of usufruct laws.

Proudhon also wrote On the Principle of Art (1865), a treatise on the social role of art and artists in society. The artist Gustave Courbet served as a role model in the book. Courbet himself was inspired by Proudhon’s system of mutualism, installing a Federation of Artists during the short-lived Paris Commune in 1871. Courbet visited Spa on several occasions. A series of drawings are testimony to those visits.

vitrine

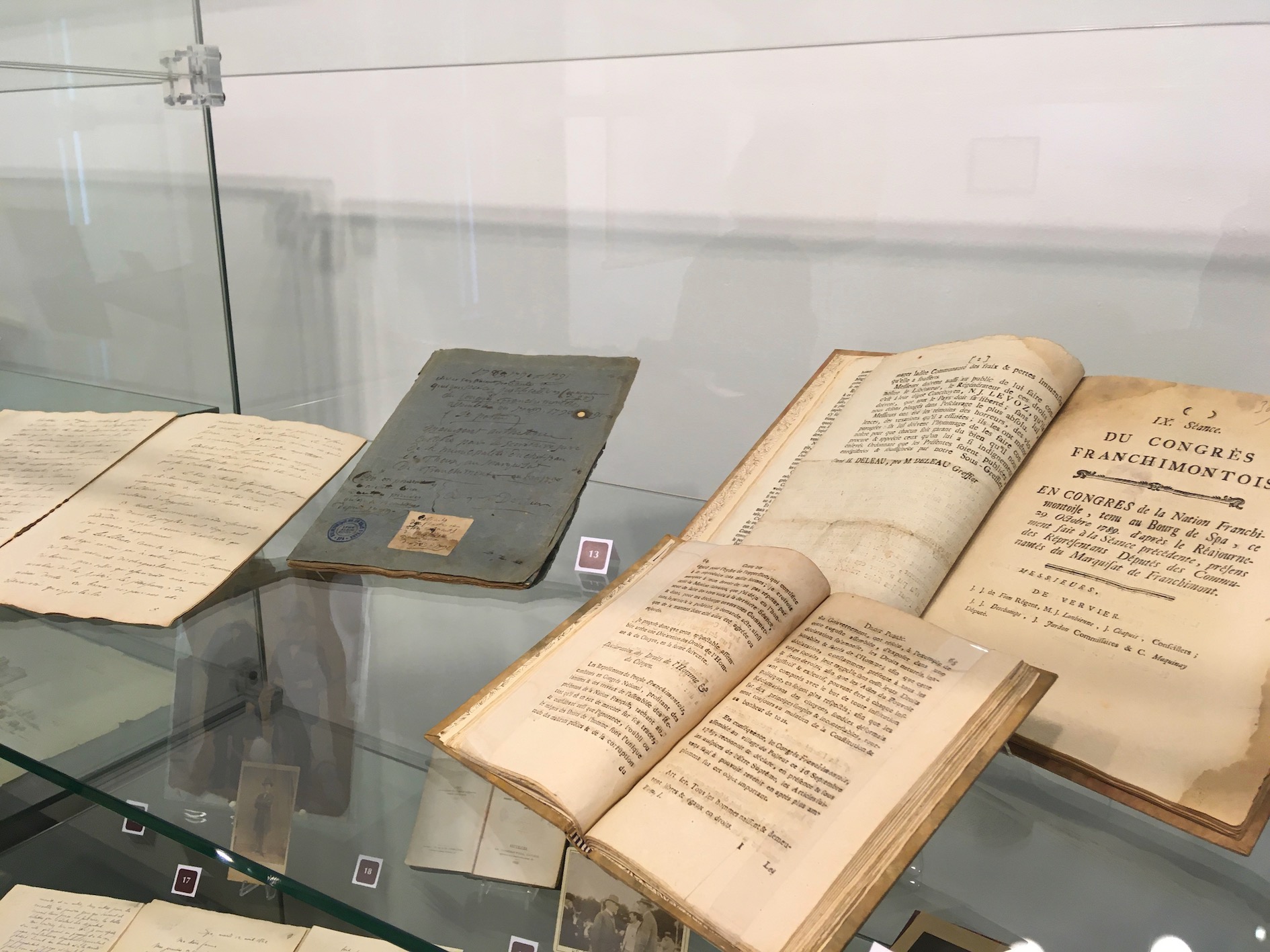

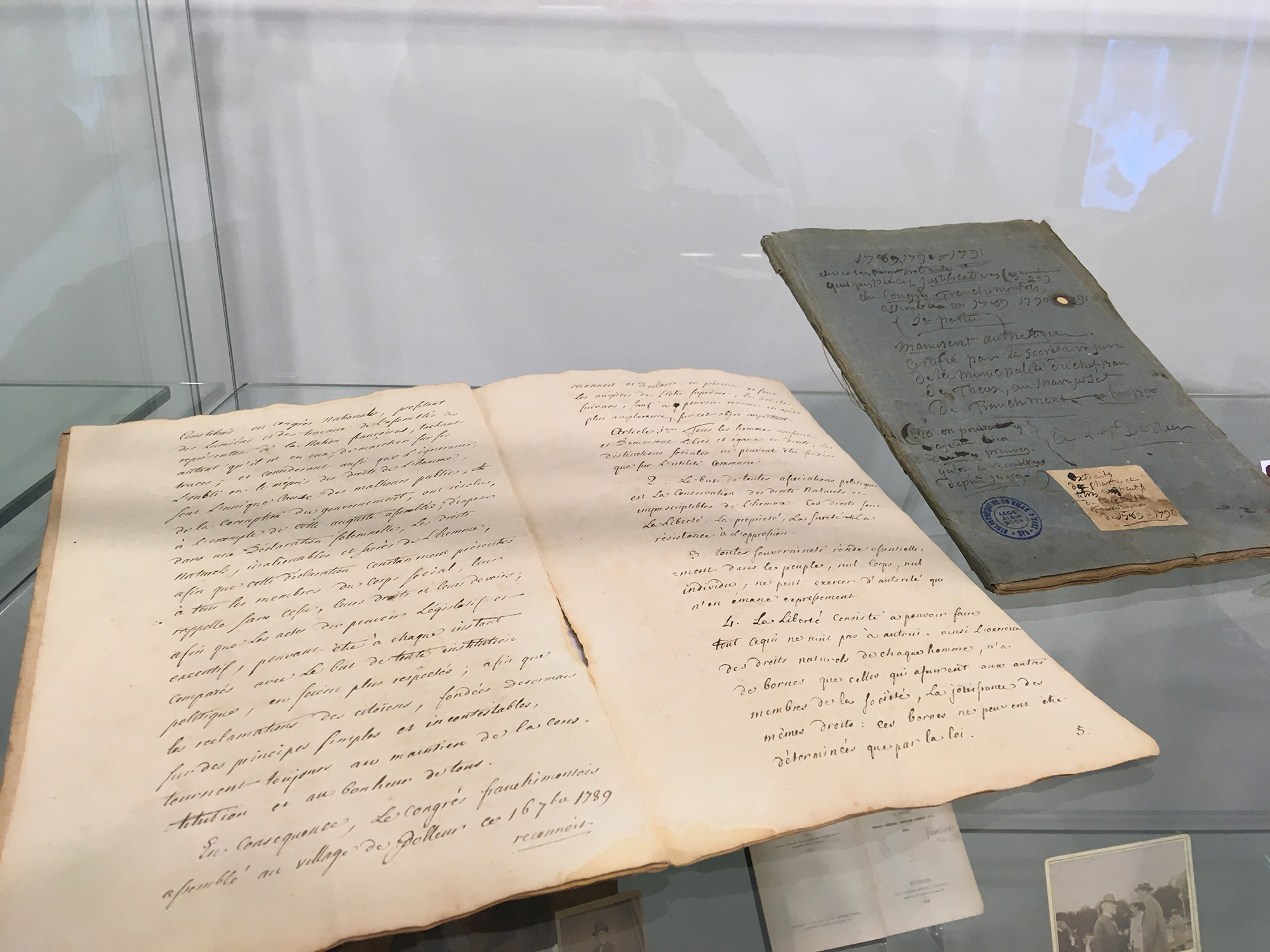

12_Congrès de Polleur: original handwritten document ‘the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen’ that was presented by Laurent-François Dethier on 16 September 1789 during the Congres of Polleur. The document addresses the rights of man for all humankind, a rupture with older texts addressing rights of specific groups in society. The text proposes articles expressing liberty, equality, security, natural rights and the right to property. Inspired by the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, it was in some respects even more revolutionary. For example, Article 3 states that sovereignty resides in the people, not in the ‘nation’ as is the case in the French text. Article 5 proclaims a proportionality of taxes taking into account the poor. Article 7 states (without restrictions unlike the French model) that “every citizen is free in his thoughts and opinions”. The Article XVII in the French Declaration describing private property as an inviolable and sacred right, was deleted by Dethier in the Polleur Declaration of Rights. In the 18th century a citizen was foremost a property owner and therefore equality of rights clashed with de facto inequality. The abolition of this article was in harmony with Article 3 which gives sovereignty to the people.

The debate on private property was highly influential in the 18th century among the Enlightment Philosophers and found its way in the declaration of rights during the congres of Polleur. For Voltaire (1794 – 1778) a person without property could not be free. He saw in property the foundation of every social institution. Jean-Jaques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) however, saw property as the basis of corruption and inequality between people.

13_Extraits des chartes / textes justificatifs du Congrès de Franchimont, signé L.F. Dethier (1789 – 1791).

Hand copied and certified charters to serve as justifications for the Congres of Polleur.

14_Congrès de Franchimont (1789 – 91), bound miscellaneous collection of printed documents.

Right page: the ninth meeting of the Congress of Polleur in Spa on 29 October 1789.

Left page: relates to the protests concerning the closure of a gaming hall in Spa, for which 2 canons and 200 soldiers were send in to suppress it. It was one of the causes of discontent leading up to the Liege Revolution in 1789.

15_Ode du droit public du pays réunis de Franchimont, Stavelot et Logne. Tome 1 / I (1795)

A printed version of the Polleur Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen.

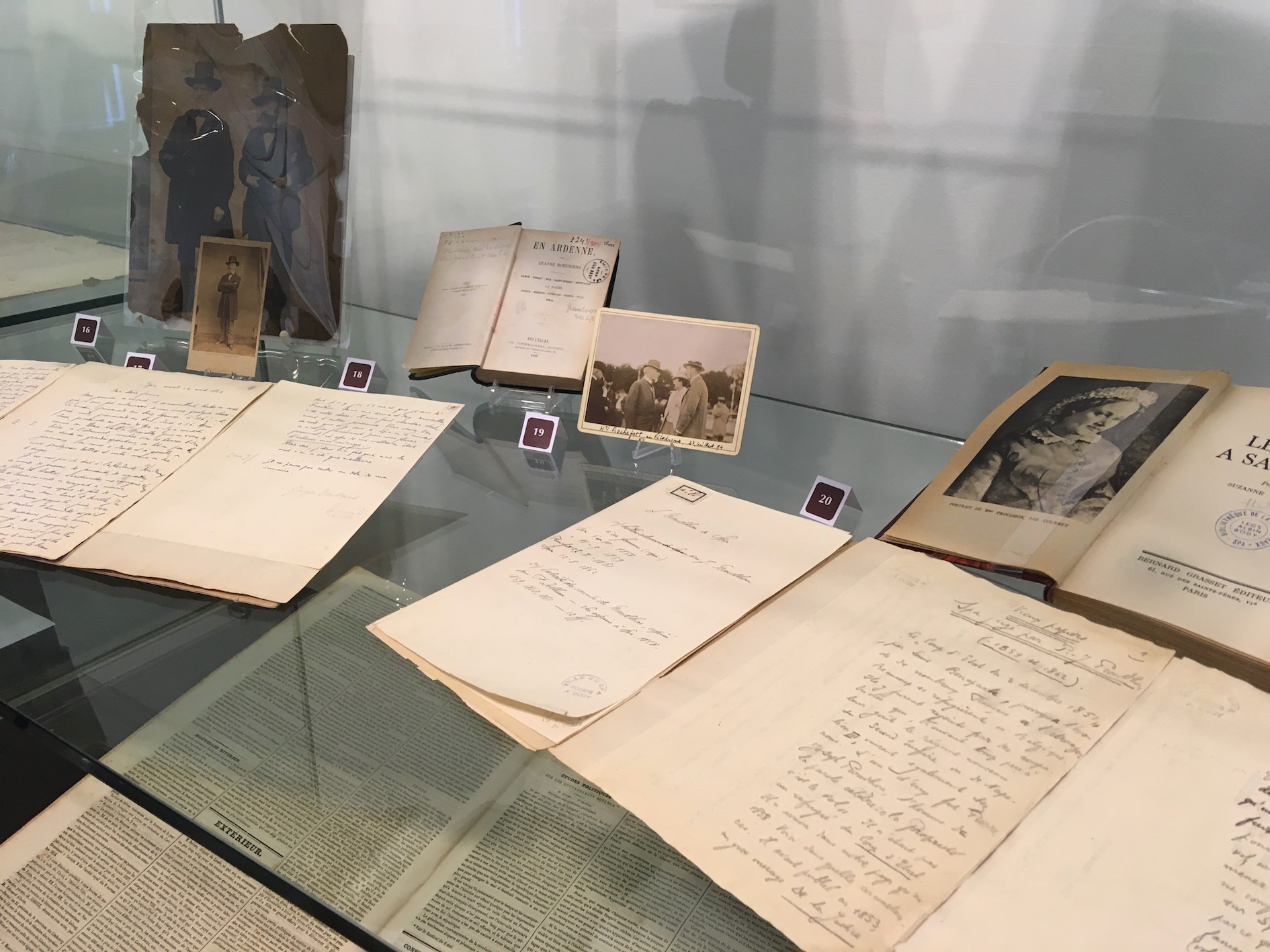

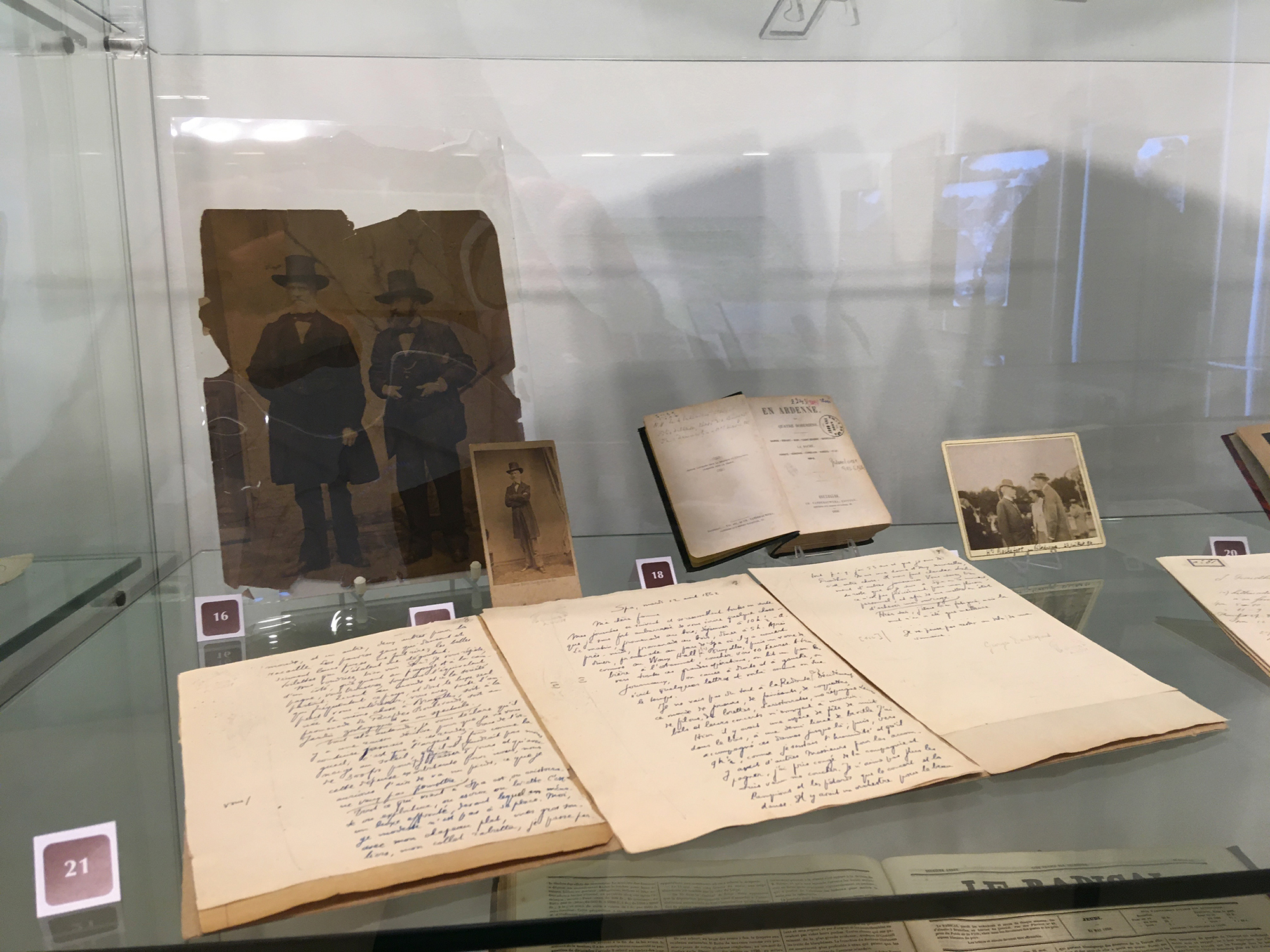

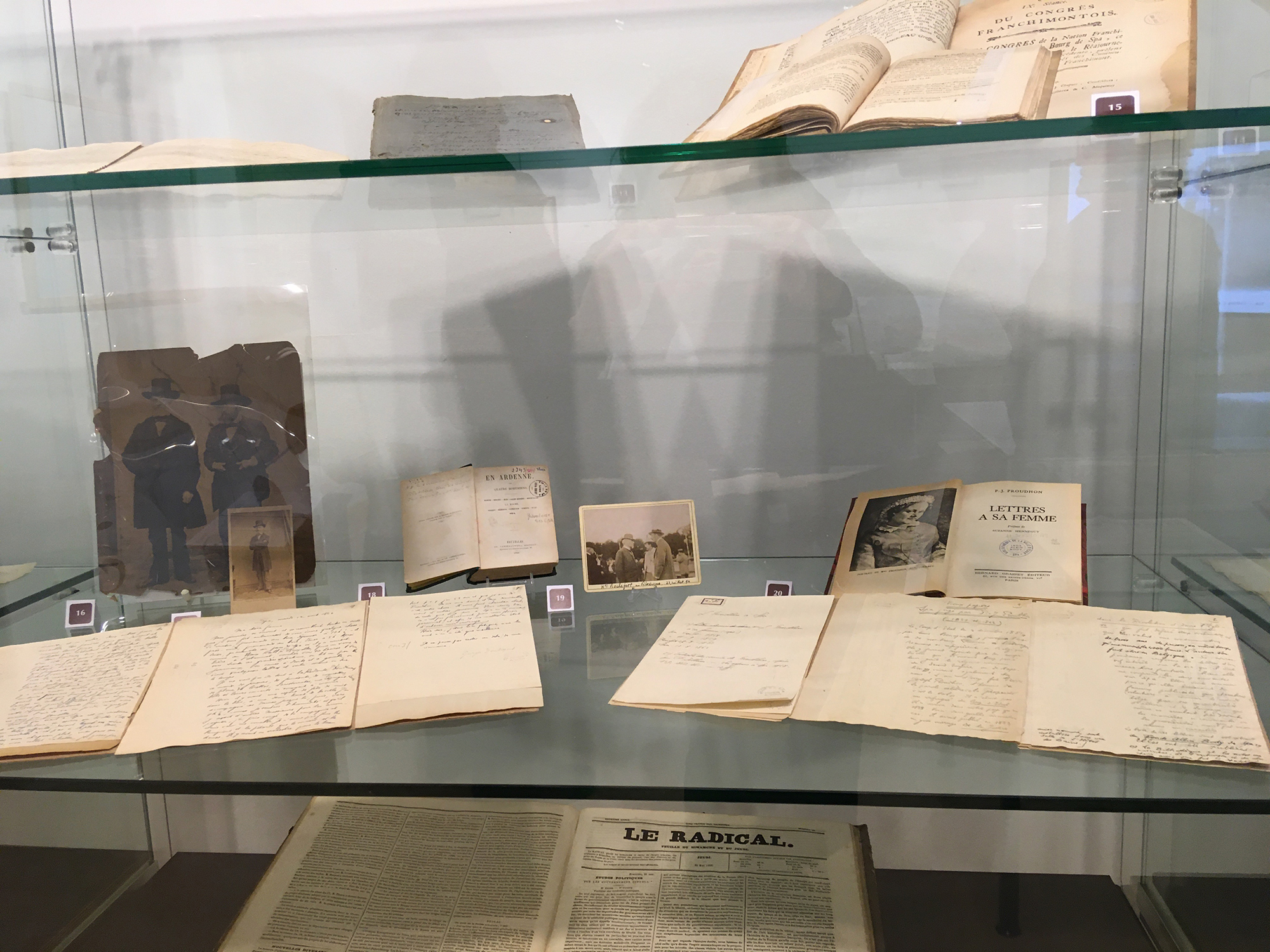

16_Théophile Thore-Burger and Felix Delhasse: Photo

17_Felix Delhasse: Photo

18_Delhasse, Thore-Burger, Dommartin, Marcette: En Ardenne, par quatre Bohémiens.

Namur, Dinant, Han, Saint-Hubert, Houffalize, La Roche, Durbuy, Nandrin, Comblain, Esneux, Tilf, Spa, en collaboration, (Bruxelles, Vanderauwera, 1856). Delhasse and Thore-Burger wrote together under the pseudonym Jacques Van Damme. Thore-Burger was a journalist and promotor of the revolution of 1848 in France. Like Delhasse he was affiliated with la Charbonnerie and dedicated himself to the democratic movement. He is best known as art critic, promoting realism, like the work of Courbet. He became famous for his re-discovery of the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer.

19_Henri Rochefort at the Velodrome in Spa in 1894: Photo

Henri Rochefort was a radical journalist and French politician, criticising Napoleon III in his polemic journal La Lanterne. La Lanterne was one of the forbidden journals for sale in the Cabinets de lecture in Spa ran by Bruch-Marechal.

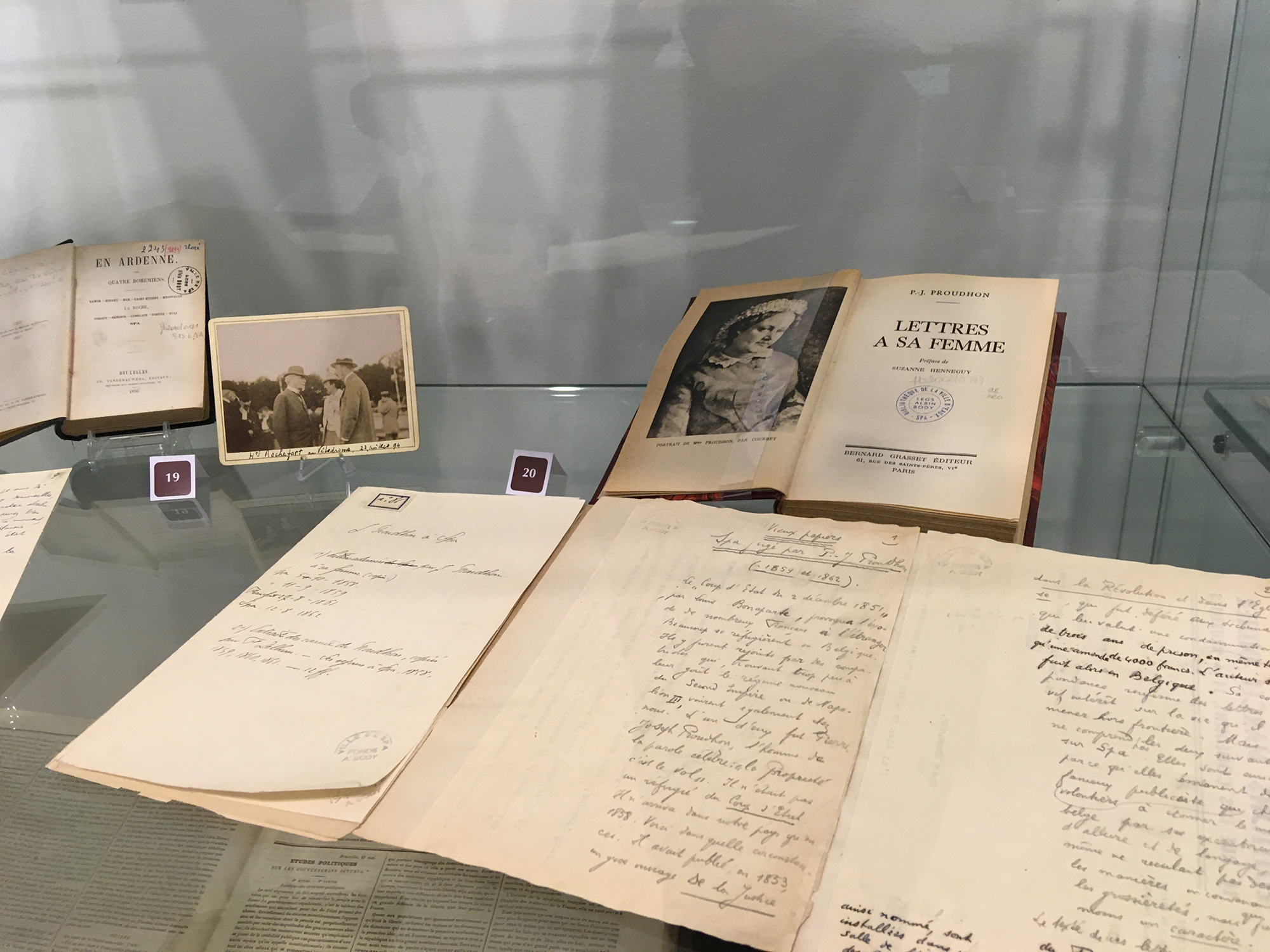

20_Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Lettres à sa femme (Paris: Grasset, 1950).

Illustration: Gustave Courbet, Portrait de Mme Proudhon.

21_Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Lettres à sa femme (12 August 1862).

Transcription Felix Delhasse

22_Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Spa jugé par J.P.Proudhon (1859 and 1862).

Transcription by Felix Delhasse

23_Le Radical (1837 – 1838)

The Spadois Alexander and Felix Delhasse were political journalists. They were among the founders of the Brussels’ journal Le Radical (1837-1838). May 24, 1838 Le Radical published Conspiration de Babeuf pour L’egalite. Grachus Babeuf planned a coup on the French Directory in 1796 to restore the progressive constitution of 1793, which was never implemented after the execution of Robespierre in 1794. Robespierre rose up against the bourgeois class, which wanted to confiscate the French Revolution for its own profit by the constitution of 1791. For Robespierre political equality was nothing but the means, while social equality was the true goal. The Manifesto of Equals, written by one of Babeuf’s co-conspirators advocated a radical reform of France which went further than the French Revolution’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen to enforce the practice of absolute equality across all aspects of society. It placed a strong emphasis on the abolition of private property and equal access to food. The manifesto further denounced the privileged bourgeoisie who benefited from the Revolution such as the wealthy landowners who continued to profit off the ‘common good’ of land. Filippo Buonarotti, a co-conspirator to this failed coup, narrated these events in his book ‘The History of the Conspiracy of Equals’ (1829) which he wrote during his exile in Belgium, at which time the brothers Delhasse became his disciples in the secret society La Charbonnerie he had founded.